A Social History

Part Three: A Place of Belonging,

A Place to Belong

A Changing Building

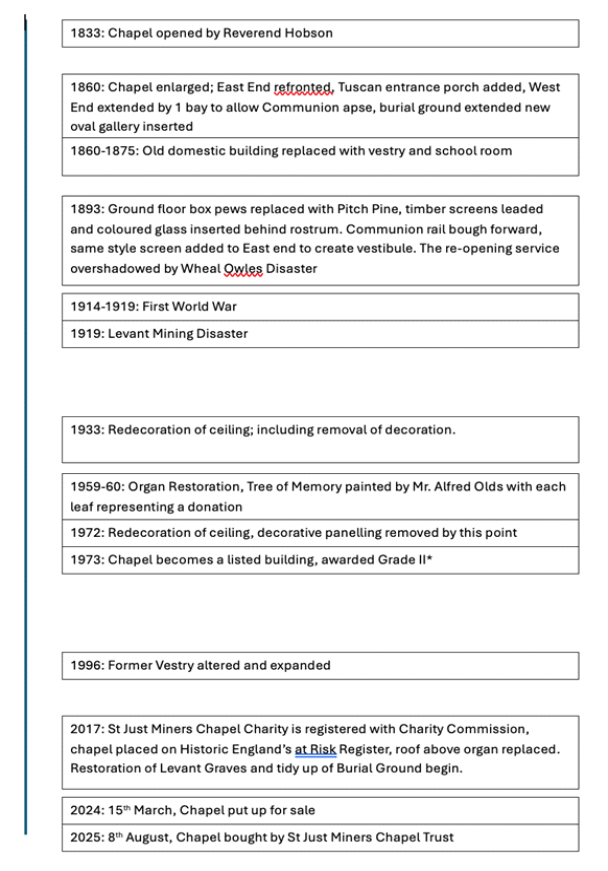

Brought about by necessity or changing times and tastes, the work to extend or maintain the Chapel has been carried out by local companies and therefore local people whether paid or voluntarily. The Chapel was refurbished in the 1850s, extensively remodelled and enlarged in 1860 when it gained its new frontage and its gallery, re-seated in 1892, with further work being undertaken in the 1930s and 1940s. At some point in the past couple of decades the roof covering has been replaced, rotting window frames, rotting fascia boards have been replaced. In this sense, its physical fabric reflects the changing fortunes of St Just, as well as a considerable amount of continuity. The following section attempts two things; a timeline of the changes and the stories that accompany.

There is an image of the chapel undergoing maintenance in the 1930s, carried out by Willian Trezise’s company, faces of the workers include a Grandfather, an engine driver at Geevor by day, who would join in the Chapel maintenance taking place in the evening light. Savvy to the costs to the Chapel, the timber used to support the work on the ceiling was laid upside down, as to not wear the tongue and groove, so that it could be reused and cost the Chapel nothing. Scaffolding platforms aside, much of the work on the great building were nothing short of feats of daring-do.

Working in 50s/60s a young Bryan Cuddy would help paint the fascia boards, no scaffolding; three sets of wobbling, wooden ladders. Robert Matthews got halfway up and froze in fear, Bryan had no choice but go up and put his arms round him to bring him back down.

Anyone who has braved the lofting heights of the roof space deserves a medal. They return with stories of the roof resembling an upside-down ship made of 64ft stretches of pitched pine, or the discarded galvanised sheeting still laying aside from when the gas lighting was replaced by electric, gone now perhaps but the steel pipe leading from the central rose through to roof space to cowl is still poking out of the roof covering. All forming part of a sort of archaeological dig in the clouds giving evidence to the middle decorative rose that once formed part of the ventilation system. The gas, powered by the Holman Factory and the Organist, who had the additional job of opening the vent via a pulley system situated by his side to relieve the sweating walls. An estimation for the removal of the gas system and replacement of electric was given in 1944, the work completed in 1947.

“You were putting new windows in the front of the chapel, and you called me, and I went up and you were on top of the portico, and you said look at that, and you said you couldn’t put a penknife blade between those stones.”

“If you look at the picture of the chapel, the three middle windows, there’s an arch, the stonework inside of that arch is absolutely unbelievable. Even better than the stuff around, and those are roughly hewn stones, in the wall but there’s no shrinkage cracks, nothing.”

It’s 2017, the roof above the Organ has become dangerously unstable as the fascia boards had rotted away. One more high wind and it will be blown off and the Organ will be ruined. H. Matthews are contacted and erect scaffolding to protect it and the interior of the chapel now looks like a construction site and not becoming for the wedding taking place this weekend. Resourceful, the Trustees band together and purchase yards and yards of white muslin, draping it around and over the austere poles and somehow, miraculously, creating the illusion of beauty.

You can’t see it now; the Communion Window is boarded up and no longer looks out over the fields and towards the sea. If you could see it, you might read the timber Commandment tablets, or read the scripture beneath; “This do in remembrance of Me.”

Congregations

The Chapel was built to house the growing congregation of St Just Wesleyan’s. Reports of 1000 or more filling the pews are not hard to come by. In those days, a family from Botallack would have to leave early to walk over in time to get a seat. It is supposed that the congregation began to fall again following the First World War, and again the Second World War, when men returned with a slightly different view on the world than they had when they left. Perhaps another turning point was when motor cars became a more affordable option for families, and developments in communication; the television for instance, introduced new ways for the community to find entertainment.

If pews could talk, they would whisper the names of the families that sat amongst them. Of those who paid their pew rental and had their names etched into brass plates that slid into the doors to say who lived there. They would tell of those who scratched their initials into their wood, graffiti yes, but a lasting tattoo of remembrance. Perhaps they might tell us who caught whose eye one Sunday evening and the tales of courtship that began here and ended with the Chapel full for their wedding a year or so later. They could recount the baptisms, new life for the congregation and fuelling the Sunday School, and yes, count the tears shed during the funerals of those now laying at rest in the burial yard. And perhaps they might tell us too, why the local Police Constable had his own designated pew on the ground floor, at the back on the left…

Alfred Olds is delivering milk for his father. A Sunday, the small boy balances a 2.5-gallon bucket on his bicycle and pedals hard, to get back to chapel on time.

A family sit in their pew ready for the service, dressed in their best clothes; the children wait for their father, who today is part of a parade, to appear in the middle aisle. They spot him, watching as he draws level with them. He grins at their mother as he opens his coat and displays all his pistols.

A Preacher stands in the pulpit, he is recounting a story from his week. Walking through a field he sees a bull charging towards him. He orders the bull to “stop in the name of the Lord”, and watches in wonder as bull came and knelt before him and he rested the bible on his head. He tells the congregation that “If you don’t believe me then leave the chapel now,” A wife hastily pins her husband down.

A young man sits in his family’s pew in the Gallery. They are listening to the service with one eye on the window looking out towards Truthwall for the first sight of the bus, if they wanted to catch it, they would have to leave now, to beat the crowds exiting the chapel, so that they could go to Penzance and walk the Promenade as they did most Sunday evenings. But tonight, the Minister is taking his time, with a little dismay, this young man and his friend have caught wind that the Minister has twelve pages of notes to direct his sermon, and they must come to terms with the fact, that they will not reach Penzance this Sunday.

Another Minister is also careful to take his time, not because of lengthy notes, but because he has poor eyesight and issues with his sinuses. He pauses in his service, removes his jam jar glasses to polish them, takes the opportunity to blow his nose, replaces his glasses and picks up his service again.

The last time that the Chapel is remembered to be full, is the St Just Circuit Rally in the 1950s, or 60s. The 17 chapels within the Circuit came, for tea, a concert and hymn singing. Each Chapel had to choose a hymn to sing the first verse of. Our Chapel congregation always sat in the middle of the Gallery, awaiting their turn which was traditionally last. When they sang, everybody joined in for the rest of the hymn.

In c.2011 the St Just Circuit was merged back in with Penzance. It was the end of a resident Minister for St Just. On the last night of his service, a congregation member sits alone in the Gallery. He is asked why he chose to sit there and replies to the Minister that he wanted to sit in the pew where he once sat with his mother and look to the other pews where his family and friends had surrounded them.

Levant Mining Disaster

In October 1919, bells are clamouring across the parish of St Just. Miners have dropped tools and hurried to aid in the rescue efforts at Levant. Unable to free the trapped miners via the collapsed Man Engine, they are scaling cliffs to reach them through adits. As the days go by and the rescue efforts draw to a close, St Just is silent.

It’s 2017, the McFadden’s have offered their services free of charge to start clearing the jungle of aster and laurel that has swamped the Chapel Graveyard. They cut back a bramble covered headstone and to their delight, they have found Granny. Bryan Cuddy has typed up his father’s records and entered them into a database. He now has the location of the Graves for the 4500 people buried at the Chapel, thanks to meticulous records kept by his Undertaker and Carpenter father. As it approaches 2019, and the 100-year anniversary of the Levant Mine Disaster, the combined efforts of the Chapel team mean that each of the 15 miners that were buried at St Just Methodist Chapel can be found, even that of William Ellis whose grave was hitherto unmarked. The anniversary is marked with a service, stones to mark their graves and a plaque that joins that in remembrance of the Wheal Owles Mining Disaster in 1893 where 26 miners lost their lives.

A Near Miss

27th September 1942, the Luftwaffe are flying towards Penzance hotly pursued by the RAF who take aim and fire at the German Dornier bomber as it heads over the town of St Just. The residents of St Just, alerted not just by the air raid sirens, but the sound of the gunfire and aircraft engines overhead having taken cover under tables, or in backyard shelters, huddled waiting as the aircraft skims the roof of the Old Chapel Sunday School, leaving a scar visible to this day, before finally crashing into two homes on the convergence of Chapel Road, Chapel Street and Boswedden Road, almost directly opposite the Chapel itself. It seems to the residents of St Just that the whole of Chapel Street is ablaze. One German Pilot parachuted to safety, picked up and arrested by a farmer in Kelynack, the remaining three perish in the wreckage.

As the new day dawned the damage to the town becomes obvious, aside from the two houses completely destroyed, windows across town have been blown out, roofs damaged, half the town cordoned off by the Home Guard, but miraculously no civilian casualties. Parts of the wrecked aircraft were scattered about the town. And, unfortunately, so were the remains of the German Crew. A body blown in through a bedroom window, an eyeball found lying in the road by curious children looking for relics, and a leg, found days later on top of a bedroom wardrobe. And yet, despite the widespread damage to the town, the largest building, unconscionably close to the point of impact, was left undamaged and the only change to the building as a result of the war, was removal of the iron railings[1], leaving lead socketed attachment points empty around the town. Iron railings were removed from towns as part of a patriotic ‘scrap drive’. Iron for tanks, battleships, bombs and shells. Most of it was never used, as was also the case with the aluminium pots and pans donated by housewives to make Spitfires. It was the wrong type of aluminium.

[1] Knifton, (2015)

The Sunday School

Until the late 1970s, the old chapel is in use as a Sunday School. Three teachers with ten-twelve pupils in each class would meet every Sunday afternoon after attending the service at the chapel in the morning. Prizes of books are given out for attendance. Bible quiz competitions are held with neighbouring Sunday Schools. The teachers are remembered for their quirks, a reminiscence of a ‘hard of hearing’ teacher gently teased by boys pretending not to talk and causing him to pause to remove his hearing aids and check they are working. There is a ‘one piece bizarre’, a gentleman on the boy’s floor trying to sell items that ‘men’ would be interested in, but the eleven-year-old pupil cannot yet see a use for a wet shave razor. At Christmas there would be parties, and halfway through Nicky Harvey would arrive from his baker’s shop on Fore Street with a great tray of pasties. Tea Treat outings continued as they had done in the previous century, with expeditions for example, to Carbis Bay beach by Coach. Pupils would be taught, encouraged and remember performing, songs or passages standing on trestle tables to recite, girls dressed in little white dresses, white socks and sandals.

Little pretty dresses, white socks and sandals is a memory that is also attached to the many social activities of the Sunday School and Chapel.

It is the 24th of July, a Thursday this year and the schools are therefore closed as the Midsummer Parade is about to begin. The pupils of the Wesleyan Sunday School are gathered outside on Cape Cornwall Road awaiting the arrival of the brass band, it is their turn this year to lead the parade. With their banner held high, they lead the way, out to West Place and the top of Bosorne Street where they would pick up the Bible Christian Sunday School. Then down to the Free Church, up Green Lane (South Place), down through Gear Lane, through the Square and into the Plen-an-Gwarri to hear the service. This year Harry Rosee, a Congregationalist minister who spent most of his ministry in Callington, has returned as he does every Midsummer to lead the service. In fact, the population of the town has swelled visibly, people have returned home for Midsummer as they might do for Feast, or Christmas. The Sunday Schools sing a rousing rendition of ‘Summer Suns a Glowing’ as they do every year come rain or shine.

The parade leaves the Plen-an-Gwarri, crosses the Square and heads down Nancherrow Terrace, up Chapel Street, down Cape Cornwall Street, through Princess Street, up Bosorne Road, back through Queen Street and then arrives back at the Sunday School. Outside, they sit on the grass and eat Tea Treat Buns, a saffron bun ‘as big as your head’ and play games. The girls study their white shoes and socks, blackened now by the parade on the hot, melting, tarmacked roads of St Just.

The Midsummer Parades came to an end when the Sunday Schools began to close in the 1970s, ending completely in the early 1980s. Attempts to revive the parade, to open it to all and not just the Sunday Schools, start and wither away again; later it is replaced by Carnival, and later again by the Lafrowda Festival, the current community celebration day. The Old Chapel closes its doors and is sold, but the Sunday School is moved to the Chapel and takes on a new lease of life. The pupils of the ‘Old Chapel Sunday School’ are now fifteen years of age and are running the classes that take place in the ‘Vestry’ as the service runs in the Chapel. This part of the building is ‘a little grim’ but is renovated in 1997 with a new kitchen, a larger footprint and nicer toilets. New Sunday School teachers have taken up the mantel, and teach from the suggested Methodist Publications, stories, materials; what you could sing or draw that taught the message of the sermon delivered next door. A small play might be practised, and the young pupils hustled into the main chapel to perform their learning on the pulpit.

If music be the food of love, play on

It is a wedding day at the Chapel. The bride is looking nervously out of her window, not because of the momentous day ahead for her but because a storm has blown in, tremendous winds, thunder and lightning were not what they had ordered for the day. As their neighbour’s dress and make their way to the Chapel for the service, they are pulled aside. The electric has been cut off, the only way to power the organ is the old-fashioned way; “Mr Hattam, would you mind terribly…” The children watch as their smartly suited father steps into the magical space behind the organ. Entranced, by the sound and sight of the matrimonial service taking place, they almost forget that the only reason the organ is playing is because their father is making it happen. They remember swiftly enough though, the sight of him climbing out of that magical space, tie and jacket removed, collar loosened, dripping in sweat.

The Organ, as well as the Chapel itself has a history. The current organ is not the original; despite being restored in 1959/60, it was replaced by the organ from Trewellard Chapel after that closed down and the original organ ‘died’ in the 1970s.

The Choir has gathered in the Vestry and are now make their way up to the Choir Stalls. In the Gallery Pews, eager children look towards them, finding their mother’s face, wondering at the magnificent hats or imagining that they magically appeared from the two rooms behind the organ. This Choir meet for practice every Wednesday, more if they were preparing for an event such as Feast, or Easter. As the organ begins, they stand, ready to fill the Chapel in harmonic chorus.

The Choir is of the Chapel, but is a social group of their own, gathering together for Choir dinners, responding to requests for concerts away from their home Chapel. There exists a recording of the Choir, singing not in the St Just Chapel but in the neighbouring Trewellard Chapel. At the request of Willy Eddy who was home from America, the choir sings “Bless this House” as he prays during the Harvest of the Seas Service that he organised.

Sadly, the Choir seemed to fizzle away during the 1970s, but that doesn’t mean that the Chapel has been devoid of the sound of voices in harmony. There have been, and are, a number of notable events that have kept the building alive with music. In any year, the Chapel is home to musical events such as the Mayor’s Charity Concert, host to the Mousehole or St Buryan Male Voice Choir and Pendeen Silver Band. The St Piran’s Parade have their concert here, and International Male Voice Choral, biannual concert here. These are events that continue to bring the community together.

July 2019, a beautiful summer afternoon and I have returned home from work early and I’m washing dishes. My rather melancholy meditation is interrupted by my eight-year-old son who wants to know what the noise from the street is. I take his hand and decide that we are going to go and find out. We head down Fore Street, following the sound of the drums that are emanating from the Square. A Choir has gathered, entranced we watch, listen, oblivious to the reason for this gathering. I see a familiar face and ask what’s happening. It’s the Langa Choir, they say, over from Cape Town, fresh from Glastonbury. There is movement, the Choir are dancing, they are singing, they are making their way out of Market Square and heading towards Bank Square. Behind them, we follow, the town follows, as if bewitched by their song. We follow them down Chapel Street and in through the doors of St Just Methodist Chapel. And as we move with the music in the gallery, we are grateful to the skilled workmanship that took place over 100 years ago, safe in the knowledge that the pillars will take our weight.

The volume of the singing, heard for miles, over centuries. You have to be there to feel it, not just hear it. Following the concert of the Oggymen in November 2024, not just a few tears were shed from the emotion of the packed Chapel. There will be more about music in the coming sections, but we will pause here to ask a question; is it true that Dame Nellie Melba during her farewell tour of Britain in 1926 sang from a purpose-built platform placed on top of the pulpit?

Hireth: A Place to come home to

In a previous section we have discussed the great emigration, those hundreds of thousands of miners and their families who left Cornwall when the mining economy crashed during the 1800’s. But for those families, and their descendants, the Chapel has remained as a beacon, a place to turn to and remember. Hardly a week will go by without someone arriving, looking for information on their ancestors, perhaps a grave to pay respects to, or a place to sit where once their family sat. The closest that they come to touching history.

These people come from across Cornwall, across Britain, they come from America, Australia, armed with names that are still familiar in the town. They support the Chapel from afar. It is their home to come back to.

When the Miners Chapel began fund raising to secure its purchase, the donations came in from; St Just, Pendeen, St Ives, Hayle, Penzance, Marazion, Camborne, Perranporth, Falmouth, Truro, St Agnes, Helston, Wadebridge, Launceston, Liskeard, Callington, St Austell, Par, Bude, Newton Abbot, Plymouth, Stroud, Bristol, Bromsgrove, Wrexham, Caemarfon, Llanymynech, Tonypandy, Woodhouse Eaves, Baldock, Highbridge, Hitchin, London, Swindon, Woking, Brighton, Eastleigh, Evesham, Houghton le Spring, Belvedere, Warwick, Worcester, Taunton, Loughborough, Sheffield, Leicester, Westbury, Birmingham, Leeds, Buxton, Loughborough, Bedford, Peacehaven, Nottingham, Cranbrook, Jersey, Ravenshoe (Australia), Tura Beach (Australia), Oregon (US), Michigan (US) and Maryland (US). And whilst geographically distant, these supporters remain spiritually present.

In memory of my Hosking family buried in the churchyard and my great grandfather, Wm. Henry Hosking, who lived in Pleasant Terrace in 1866.

In memory of Annie Hill Roberts and Ralph Hill Roberts, all my other ancestors and relatives who are buried here and to the mining community of St Just.

The Miners’ Chapel means so much to me. My Great Grandad Edward Bennetts was the chapel-keeper back in the late 1880’s. and the family lived at Victoria (is it Avenue?) New Downs, St Just. They were a mining family originally. My Granny, Mary Ancell Bennetts, their daughter, was married in the Chapel just after WW1 to my Grandad Ralph Hill. who she had nursed (she was a VAD in Bristol) after being wounded at Gallipoli. He farmed near Totnes, in S Devon, so that’s where I remember her when I was a little girl. Most of her siblings went off to America in the 1900’s and so we have relatives in California, and Michigan. I like to think of them all when I come down to St Just each year to visit my Great-grandparents grave. I have lived in Somerset all my life, but feel Cornwall, especially St Just, to be my spiritual home! I would be devastated if anything bad happened to the Chapel.

Hospitality and Social Activity; A Building that wants to be used, to be loved

It’s Harvest Festival, a small girl is taking her turn to take her offering of fruit and vegetables up to the Minister. On top of the offering a bunch of grapes are wobbling perilously, before a few take a tumble, and she watches in dismay as they fall from the dish and into the metal gratings in the floor. The Chapel is full of fruit and vegetables, the ceremonial harvest loaf taking centre stage amongst small, crepe paper decorated baskets of strawberries. The Chapel’s pillars are decorated with sheaves of corn, and following the festival there will be a concert, an auction of produce and of course, the harvest supper.

The Methodists have always been renowned for their hospitality, it is a central tenet of their belief. Every Chapel had their own decorated china sets, the Wesleyan design a deep maroon in colour. The harvest festivals of neighbouring chapels never to take place on the same day so that they may travel around and enjoy each other’s celebration. Whilst the congregation attending services might have dwindled over the last century, the social and hospitable doors have remained fully open. The list of activities that have taken or take place is considerable and this next section will try and elucidate that the Chapel is a base, not just for religious life but our social life too.

In its more distant past, the social life of the Chapel was centred around assorted Guilds and Fellowships, remembered now by the grown children who were only allowed to attend special events, unlike their parents who attended the weekly meetings. The ‘Winking’ game, or ‘Cod, Shrimp, or Whale.’ Nobody quite remembers the rules, but they remember the energy, the fun.

In its more recent history, the Vestry has been home to a youth club, catering for children up to the age of 11 from whence they would graduate to the Nancherrow Youth Centre. The Boy’s Brigade was housed here. There was (and this is by no means an exhaustive list) a Breakfast Club on a Monday, aimed at young mums after dropping older children at school but attracting a wider, more mature, audience, Tuesday Afternoon Story and Tea gatherings (perfect for sharing memories), Soup Lunches, Musical Munch, Porridge with Prayer and Messy Church, an initiative jointly run with the Parish Church that still runs today. Fondly remembered are the monthly dress-up occasions; themes include Cowboys, Pirates, Dad’s Army, Last of the Summer Wine, Alice in Wonderland to name a few. Many of these activities suffered first due to the amalgamation with the Penzance Circuit and the resultant the loss of an enthusiastic, permanent minister, secondly the lockdowns that occurred during the early years of the Covid-19 Pandemic, and thirdly due to the increase in legislation regarding Safeguarding and Volunteer activity, necessary, unfortunately but burdensome.

The Chapel is home to many annual events, concerts as already discussed, but featuring high in the calendar is the Annual Christmas Tree Festival. A sight to behold, as the various community groups in St Just decorate a tree to a theme on a single morning in December to be enjoyed by the whole town as they file in throughout the Christmas period to enjoy the sight of 24 twinkling trees amongst the pews. It’s become a tradition, the concept rescued from neighbouring Sennen after it ended there. Open from the day of decoration to New Year and only closing on Christmas Day itself. Beloved by the community, and the perfect backdrop for the season’s services. The perfect example of doing for the love of doing.

Creatively, the Chapel has earned an international reputation, with acoustics and capacity of a size and scale that has welcomes huge crowds to extremely successful performances and cultural events.

In 2018 David James opened the doors to the Chapel, it’s only illumination the backlit pulpit. The atmosphere was enough to convince Ed Rowe (the Kernow King) that this was the place to stage his now award-winning play Hireth, written to mark the centenary of the end of World War One. The production told the story of Cornwall’s forgotten war heroes, those who swapped the “dirty, dark and dangerous tunnels of Geevor for the deadly underground warzone beneath the Western front”. Speaking later Ed Rowe said;

“We knew Hireth would require a sizeable venue, but nowhere seemed to quite fit the bill…we needed somewhere very special. Magical, almost. I stumbled on The Miners Chapel in St Just after a recommendation that I check it out, and what can I say? I fell in love straight away! …as soon as I stepped through those doors, I knew Hireth (Cornish language meaning longing for home) had to be there” Edward Rowe, performer, playwrite, Cornish legend

It remains to be said, that there cannot be a family in St Just with children attending the local schools who haven’t sat in the pews to watch their children sing Christmas Carols or attend any number of concerts instigated by the school. We will turn to their voices in the following section which focuses on the battle for the Chapel, and its future but the relationship between the school and its community is worthy of a pause. At a time when the national curriculum has become a ‘one size fits all’ plan for education, the local schools, have maintained an approach that weaves the local history of the community throughout its daily timetable. The Chapel is part of this story, a performance space for concerts yes, but it is also a classroom, ready to provide the schools with an arena in which to explore our history, and our place within the community.

A Story of Saviour: Standing on the shoulders of everyone before

Susan sits in the pews and looks towards the organ. She sees the face of her mother, before she turns and begins to play, as she did for over 50 years. Beside her, she feels the presence of her Grandmother and remembers tugging at her and needing the lavatory. This was a different memory to the time she couldn’t understand why she couldn’t talk, “he’s talking” she says, gesturing towards the preacher. Susan comes to remember these moments, she comes to sit and contemplate, to find her peace.

Sometimes, it can be just one moment that changes everything. When a lost Korean trumpeter earns £10 from a private lesson, and hands that precious money over to help save the chapel, it ignites a movement. A movement that will see the St Just Methodist Chapel taken on by a charitable trust named the St Just Miners Chapel who will spend years working to keep the doors open and secure its future.

This is a Chapel that wants to be used, this is a Chapel that is alive. Every floorboard, pew, window, granite block breathes with the two hundred years of life that has sung and moved within it.

The fabric of the building, of the echoes of the people that sat in it. You are absorbing it, the community, the sense.

In June 2025, pupils from Cape Cornwall School came to the Chapel for a workshop, its aim to gather meaningful input from young people about the Chapel, what it means to them, how it makes them feel and how they see its future. The purpose of this writing has been to capture the Social History of the Chapel, but also go further, to try and get to the heart, the soul, the sense of awe, wonder, its sense of place. It seems fitting to end with the voices of those young people who perfectly sum up the desires of the whole community, and its diaspora.

It was clear that the students felt it was important to preserve the Chapel’s history, architecture, and spiritual purpose. They wanted to protect features like the roof, organ and piano. They definitely wanted to see upgrades as well but these upgrades should be a balance between modern use and historic integrity, challenging us to ensure it is carefully managed.

It makes me feel like I need to be respectful and sensitive, about the people that have been in here, prayed here and socialised here.

It helps people unite as a community.

The history of methodism in St Just has been well documented, not least because of its critical part in the history of the Wesley brothers. As previously discussed, the disenfranchisement with the Anglican church and their ties with the wealthy landlords, coupled with the Methodist’s message of a united community and social justice, spoke to the people of St Just, becoming a part of the town’s identity that it still evident today. This is a community where belonging is as much a part of its nature as the fog laden days of summer. But it is the objective of this writing to tell the story from St Just. Of how the Chapel has been a part, a focal point, in the lives of the community. These are stories of music, meeting, humour, learning, sadness, near misses, culture, hireth. These are stories of belonging.